For cancer researcher and Dartmouth medical student Sam Bakhoum, PhD ’09, DMS ’13, a PhD just didn’t seem to be enough. “When I was young I always wanted to be a doctor but I was also interested in science,” he says.

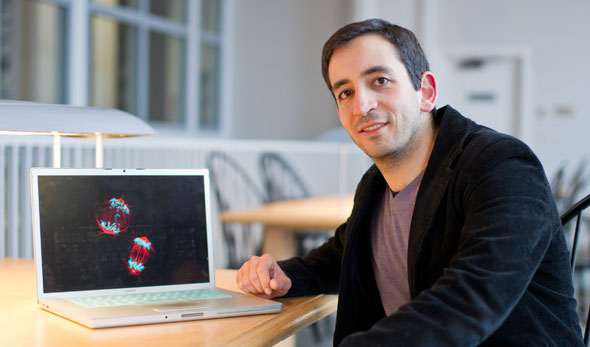

The image Samuel Bakhoum is displaying on his computer appeared on the December 15 cover of Clinical Cancer Research, accompanying the publication of his research paper on chromosome mis-segregation during cell division. (photo by Eli Burak ’00)

As an undergraduate at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, Bakhoum “fell in love with research.” This was the path he followed at Dartmouth, earning a PhD in biochemistry in 2009. But even with a doctorate under his belt, Bakhoum wasn’t ready to dismiss his first ambition.

Challenging the musings of poet and one-time Dartmouth student Robert Frost (Class of 1896) Bakhoum has returned to the figurative “Road Not Taken,” and followed the second path as well. In doing so, he is integrating the two pursuits: “To me,” Bakhoum says, “the concept of medicine is a very investigative medicine.”

The path to Dartmouth

Bakhoum’s road to Hanover has in itself been unusual and has undoubtedly helped shape his perspective today. He was born in Nigeria to Coptic Egyptian parents. Bakhoum’s mother and father, both physicians, had come to Africa to treat those in need. When he was two, with little memory of his early adventures, Bakhoum and his family returned to their home in Alexandria.

At 15, Bakhoum won admission to United World College of the Adriatic in Dunio, Italy, one of more than a dozen of its campuses worldwide. Each college draws students, on a highly selective basis, from a variety of homelands. Bakhoum recalls that his school had students from more than 80 different countries. This two-year, residential high school experience “was a turning point in my life,” says Bakhoum. “It might have gone in an entirely different direction had I not gone there.”

He developed a taste for travel and, after a visit to Vancouver, became “enamored” with the Canadian city and enrolled in Simon Fraser University. After graduating with his bachelor’s in molecular biology and biochemistry, Bakhoum embraced the Dartmouth experience and in 2009 earned his PhD in biochemistry and cancer biology under Professor Duane Compton.

Linking science and medicine

As a graduate student in the Compton laboratory, Bakhoum’s attention was on the minute cellular structures known as microtubules. During cell division the microtubules attach to individual chromosomes and guide one member of each pair into the resulting daughter cells. Flaws in microtubule function during this process may lead to an imperfect and uneven segregation of the chromosomes, a situation often associated with cancer cells.

Looking back over his PhD work, Bakhoum notes that his focus was primarily at the cellular level. “Going to medical school tied in the cell with the human body and the process of disease—a perspective I’d never previously had. Bakhoum and his coworkers are currently investigating the regulatory proteins that govern microtubule behavior as potential drug targets in cancer therapy.

“The link between medicine and science is unique,” notes Bakhoum. “I’d like to be in that position of combining both, having the medical training to equip me with the knowledge to ask the right questions in research.”

And that hope is already paying off. After completing his PhD, Bakhoum extended his findings from the laboratory to the clinical realm. By looking at tumor specimens from patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, he found that chromosome segregation errors were tightly linked to poor patient survival. Bakhoum’s work was published and featured on the cover of the December 15 issue of Clinical Cancer Research.

“This finding supports the effort to target chromosome segregation errors in cancer in order to improve survival and response to chemotherapy,” he says.