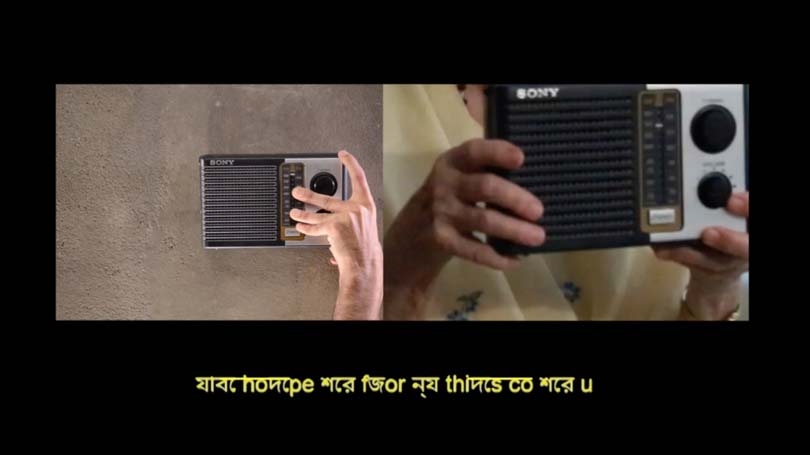

Images from Dominic Coles' installation made possible, in part, by funding from the Alumni Research Award

Leave the Needle on the Jammed Record

Across the colonized world, people resisting the oppressive forces of imperialism placed their ears against the radio receiver, attempting to decipher its noisy signal, jammed by the interference of the colonizers. In that noise was a voice obscured; they imagined its words. It spoke of independence, of fierce protests and battles; it sang national songs and anthems. These listenings would provide a tactic which would become central to the creation of a post-colonial collective politics. Listening was a means of organizing and reclaiming a collective narrative, a history, present, and future; noise was the site in which this tactic of listening could be practiced.

Frantz Fanon detailed this larger historical trend as it specifically unfolded during the Algerian War of Independence in his essay, This Is the Voice of Algeria. The radio was initially introduced into the colonial landscape as a means of disseminating colonial ideals, culture, and propaganda. With unchecked control of the information disseminated on Radio-Alger, the national broadcasting service, the French hoped to bolster the authority of their colonial powers in Algeria. Broadly rejected by native Algerians, the device was first taken up by French expatriates living abroad in the country.

A decisive shift occurred in Algeria’s relationship with the radio in 1951, coinciding with the onset of skirmishes in Tunisia. With an increase in revolutionary activity, Algerians felt the need for an expanded news network consisting of non-French sources. Shortly thereafter, the show Voice of Free Algeria was established, its sole purpose to broadcast radical, revolutionary news each day. The traditional familial resistances to the radio broke down in light of the need for information and gradually the radio was stripped of its ties to French cultural oppression. Of primary interest to my research is the phenomenon that Fanon documents next. He details the French practice of sound-wave warfare in which the broadcasting wavelengths of the Voice of Algeria would be detected and systematically jammed so that the broadcasts themselves were rendered noise. Listeners would remain, with a single interpreter, ear fixed to the radio, tuning the dial in the hopes of finding the Voice, now broadcast on a new frequency, but only to be jammed again. The interpreter would relay fragments of the broadcasts to those gathered and listening, but they were largely indecipherable. This was not a hindrance: instead, gathered listeners would imagine the Voice’s words, transplanting their individual interpretations, hopes, dreams, and visions of utopia to the scattered noise of the broadcast. As Fanon goes on to detail this phenomenon, it becomes increasingly clear that the Algerian listeners do not need to be able to decipher the Voice, rather, they gather daily to sit and listen to the radio’s noise, to the static produced by the jammed signals.

With generous support from the Alumni Research Award I was able to trace this same historical practice of listening and engaging with noise as a revolutionary tactic against colonialism as it developed in India during their own Independence movement. A combination of archival research as well interviews with family members who experienced the Indian iteration of revolutionary radio broadcasting sought to document this historical listening practice and relationship with noise.

This research took form in two distinct projects: one, a historical, conceptual sound studies essay which sought to argue for Fanon’s inclusion as a foundational noise theorist within sound studies scholarship. Attempting to decenter the normative Eurocentric tendencies of research within the field of sound studies, I center Fanon as theorist offering a similar understanding of noise as a generative and beneficial force depending on the context of its system; a theory found 25 years later in the work of cybernetic theorists Henri Atlan and Michel Serres, both of whom are primary touchstones within contemporary theories of noise. Additionally, the research manifested in a performance-installation, to be mounted in Dartmouth’s Black Family Visual Arts Center. The performance-installation engages this history of listening as it manifested in India, but seeks to explore its lasting repercussions through the process of decolonization, particularly in the violent and traumatic events that emerged after Independence during Partition. The piece seeks to understand what the implications of a widespread utopic listening practice are when historically the events following its practice included large-scale violence and genocide.

My sincere thanks to the Alumni Research Award at Dartmouth College for supporting and enabling my ability to travel abroad and conduct this research.