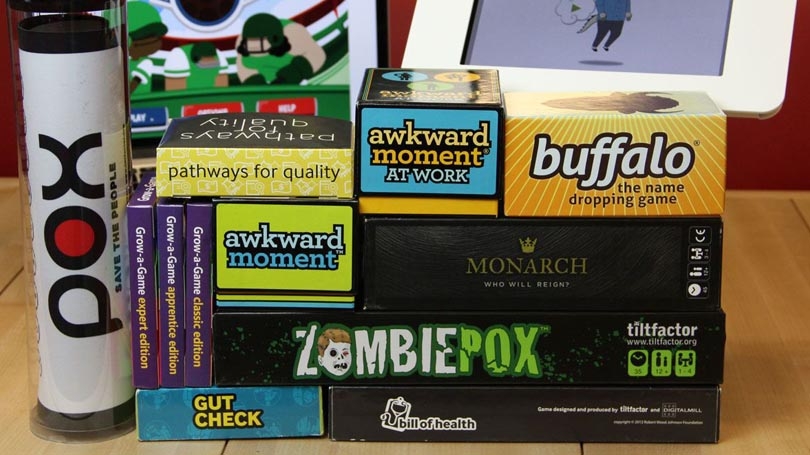

A selection of the games designed in Tiltfactor that address vaccination issues, gender bias, and discrimination.

It hurts to be told “no.” Even if you are being rejected by a computer or a group of people you dislike, you still feel the pain of rejection. Not only does it hurt, but there can also be significant down-stream consequences: one study found that thirteen out of fifteen school shooters were rejected at some point. It also has an effect on our physical response with noticeable drops in immune function.

So can we intervene and make rejection less hurtful? This was part of the conversation at a recent Brain Buzz. This monthly event is held at the Upper Valley Food Coop (UVFC) in White River Junction, in partnership with the Vermont Institute for Natural Science (VINS) and the School of Graduate and Advanced Studies. It serves as an informal science café where graduate and postdoctoral researchers can engage with members of the community about their work and the potential impact it can have on everyday lives.

Postdoctoral researcher Gili Freedman received her Ph.D. in Social and Personality Psychology from the University of Austin at Texas where she focused her research on social rejection. She began her research on rejection as an undergraduate at Haverford College where she became interested in how negative interpersonal interactions affect individuals. “When there is no script and no rules of engagement or ritual, it makes finding the right words very difficult,” explained Freedman. “We can’t use “lets be friends” or “it’s not you, it’s me” when we want to break off a relationship because they’re always used. They have become such a cliché they’ve lost all credibility.” So what do we do?

“First off, don’t apologize,” Freedman said. According to research conducted by Freedman and her colleagues, “rejections with apologies are more hurtful than rejections without apologies. Apologies are expected when the transgression is unintentional for example, accidentally spilling a drink on a stranger, but not if the situation is within the control of the person, such as rejection.” The script in that scene goes: accident>remorse>forgiveness. “With the ritual expectation of forgiveness after a transgressor has shown remorse, in a rejection situation we end up forcing the person being rejected to say it’s okay. When it’s clearly not okay!” explained Freedman.

The audience also learned of another form of rejection called “ghosting.” This is when people do not give any explanation for leaving a relationship, either in real life or online, and simply pack up and leave. Freedman asked for a show of hands among the audience for those who thought women were perceived worse when they were doing the rejecting; almost all the women and none of the men raised their hands. Men in the audience thought males would be perceived worse. It came as little surprise to learn that women are generally perceived worse, thanks to a phenomenon called “gender backlash”- when women’s behavior doesn’t conform to the gender stereotype. In the case of rejecting someone, the perception is that the woman is not fulfilling her normative role of caregiver, nurturer, etc. However, when ghosting takes place, men are indeed viewed less favorably for leaving without giving any explanation.

How and why these gender biases arise are not exactly understood, but the second part of Freedman’s work goes some way to address and, it’s hoped, change those biases. Freedman currently works in Mary Flanagan’s Tiltfactor lab at Dartmouth where her psychologist perspective informs games that are being developed in the lab to address gender bias and discrimination.

The audience played a quick round of Buffalo, a game which gently suggests bias and discrimination exist when two categories define the parameters of a name of a person that fits both. For example, the audience was somewhat stumped when the cards were “photographer” and “Egyptian.” Buffalo helps players think of counterstereotypical examples and may be encouraging players to learn more about different groups of people.

The final Brain Buzz of the season is Wednesday, May 10 when we will be hearing about the research from Dartmouth’s Toxic Metals Superfund Research Program around arsenic in our food. Save the date!